A Trip Back in Time | Who's on First? | Capt. Bogardus

Aim for the Stars | Addie Cushman

Capt. Bogardus' History

A trip through cyberspace takes us back in time

Applause, applause, for exhibition marksmen, and Adam Bogardus in particular

‘In an age when marksmanship was at an all-time peak of respectability and popularity, one of the most famed of all shooters was Captain Adam H. Bogardus," write R.L. Wilson, with Greg Martin in their very excellent "Buffalo Bill's Wild West" (Random House, New York, 1998).

They say he was the "inventor of the trap for launching glass balls and credited with the development of the glass-ball target." "Inventor? That's a bit strong, since other patents preceeded Bogardus, although it seems clear that his trap launched, so to speak, the sport of inanimate wing shooting. The writers add that "Bogardus was instrumental in creating the sport of trapshooting," an understatment if there ever was one.

Glass-ball targets and the trap for launching them evolved into clay disks (around 1880), called clay pigeons in honor of the birds they were designed to save. Unfortunately, in the late 1870s and early 1880s, millions of birds — passenger pigeons in particular — were widely decimated by hunters and, to a smaller degree — trap shooters in clubs in big cities and little villages across the United States.

In 1877, Capt. Adam H. Bogardus, already an established market hunter and an internationally known crack shot, introduced his patented target ball, a sturdy and dependable trap for throwing them, and a simple set of rules with which competitive shooters could blast away at them.

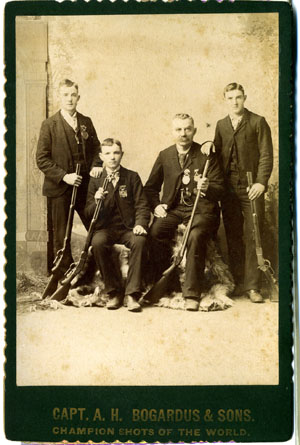

With his already established fame — he had toured England (and Paris) in 1875, 1877 and 1878 — he was tapped for even greater renown in the early 1880s when Buffalo Bill Cody hired him to join the most popular wild west show the world would ever know. With the occasional addition of one or more of Bogardus' exhibition-shooting sons (Edward, Peter, Eugene and Henry), the captain became the main shooting act in Buffalo Bill's Wild West, and would be seen by hundreds and hundred of thousands of cheering spectators.

After three years, due to business complications, personality conflicts and bad luck, Bogardus left the show and was replaced by perhaps the only person whose fame and skills could match — and even surpass — his: Annie Oakley.

But one must scour hundreds of books, thousands of newspaper clippings — many copied directly from the exaggerated wild west show press releases — to get even an idea of how impressive the truth really is.

Here is an example of what I face ...

At midnight, on a Saturday in August, 2006, while many of you were out partying (or asleep on the couch in front of the TV), I was at the computer, traveling blindly, madly across cyberspace. My destination? Unknown.

I would type in a few words, and hundreds of thousands of landing sites would arise; I would narrow the search, and head off again.

At one point — hoping to find information on the elusive-yet-famous Chicago shooting gallery run by Capt. A.H. Bogardus, I typed in "shooting gallery chicago bogardus 1879" and came up with a mere five items: one was the entire text of C.A. Bogardus' 1907 edition of *"One Thousand Secrets of Wise and Rich Men Revealed," and the other was "Captain Adam Bogardus: Shooting and the Stage ..." by Roger Hall.

My little heart skipped a beat (always a worry, since my dad died of a bad heart at 43, my grandfather at 23, my uncle at 21). Shooting on stage!

Bogardus, Paine (especially Paine), the Bennetts, Alf Malvern and hundreds of other shooters big and small (kids, too) took their marksmanship skills out onto the stage for the public to view.

Let me digress: When I was about 10, in 1950, I went with my grandmother to the huge J.L. Hudson Department Store in downtown Detroit — the store, as well as the chain to follow, is now long gone — and watched a trickshooter, up on the 14th floor, blasting away at targets. I don't remember much, but in this little cowboy's eyes he was a fast draw who could hit anything and make one heck of a lot of noise!

Maybe it was that afternoon's revelation of accuracy and showmanship that caused me to be interested in theatrical displays of shooting skills; I have spent much time trying to re-create for The Book that period in pre-1900 America where families went to witness — in village tents or big-city theatrical palaces — the often bizarre skills of traveling marksmen.

So, back to my midnight research.

Bogardus and the theater, an article written by a professor in the Journal of American Culture, Fall, 1982, Volume 5. Wonderful! More information I can borrow for the newsletter and book. Except ... except it was on the website of "Blackwell Synergy," which stated that if I wanted to READ the article it would cost me $29 — credit card, please.

Twenty-nine dollars? For what, I wondered. Can't I have a peek first? So many times I have found articles on Bogardus that are rewrites of other articles that are, in fact, rewrites of what Bogardus himself wrote in his books. I typed in the professor's name, hoping I might find his name (and article) somewhere else. Nope. I went to eBay, hoping someone might be selling an old copy of that Journal of American Culture. Nope, nada.

So, shortly after at midnight, I entered my credit card number and bought the article. But first, I had to accept several pages of legal mumbo-jumbo that said I couldn't republish the article upon pain of death. Oh, great.

HOWEVER, since much of the article included information that On Target! readers already know — where Bogardus was born, grew up, that he was with Buffalo Bill, could shoot 500 (or 5,000) balls in ... etc. — I could eliminate that material and just quote (rather liberally) the parts that were new.

And, to my pleasant surprise, there actually were parts that were not only new to me, but well written and well documented. And — trust me — I don't find that combination often. My editorial hat is off to the good professor. So, what did Roger Allan Hall have to say? Read on ...

Prof. Hall's article started off in a way that piqued my interest; and, what follows is greatly reduced (and slightly copy-edited):

‘In the late 19th century, theater audiences across the United States were fascinated with the exploits of the frontier. It followed therefore that hundreds of performers and producers fed that voracious interest with scores of delicious entertainments about frontier life, most in the form of plays. ... many of the presentations, however, were not plays."

Aw, Prof. Hall from paragraph one has me sitting in the front row of his class (a simple tactic that helped this former back-row-sitting high school C student get A's and B's in college).

Hall's comment above goes along with my emphasis in The Book that, before the rise of professional shooters, America had to first develop a middle class with enough literacy, free time, disposable income and access to transportation. The professor continues:

"Numerous performers crisscrossed America providing rapt audiences with demonstrations of Western activities such as roping, or exhibitions of Indians, buffalo, trained dogs, horses or bears. By far the most popular exhibition was shooting. Numerous shooters, billed as marksmen, sharpshooters, wing shots, rifle shots or dead shots, and generally touted as champions of one sort or another, regaled 19th-century patrons."

Hall adds that the development of the wild west shows became the home ground for shooters;

"before that, performers lived by their own talents and resourcefulness."

And, with the topic being skill and notoriety, Hall comes to Capt. Adam H. Bogardus:

"His spectacular shooting career is more than a mere curiosity; it is a microcosm for the study of several influences that intertwined in late 19th-century American society. Bogardus' work displays a pattern duplicated by many other 19th-century shooters. He began making his livelihood shooting for game to put food on his and others' tables. As his expertise and reputation grew, he found himself acting as a guide for amateur hunters and soon was participating in and winning tournaments. From that, he progressed to giving a variety of highly theatrical exhibitions and eventually became a mainstay in the arenas of the wild west shows. ... 1

"Also, like many of the other marksmen, Bogardus was not from the West at all, and yet he became a representative of frontier life. Eventually, Bogardus was affected by the changing views of society toward his own sport and by American mechanical ingenuity. As public criticism mounted toward the killing of birds for sport, he led the change to mechanical substitutes."

(Along the line of easterners and Midwesterners representing the west: The Kemp sisters had a wild west show in the 1880s-90s, and were from El Paso — El Paso, Illinois, that is.)

And, while I have attributed the growth of performance/exhibition shooting to the era's increased free time, more disposable income, access to transportation in burgeoning towns and cities, etc., the good professor points out another — and very obvious — factor, one I had overlooked:

"Appreciation for Bogardus' exploits cut across class lines, as upper and lower classes alike were awed by his shooting feats. And, because Bogardus' marksmanship wasn't limited by barriers — one didn't need to speak English to understand the report of a gun — his performances had a strong impact on America's large immigrant population and on their perceptions of American life."

While we had been a nation of immigrants prior to 1870, there was massive immigration from 1870 to beyond the turn of the century. And many of these people came from European nations already with a history and a respect for marksmanship skills. For a few paragraphs, Hall recounts Bogardus' birth and early shooting development, reading as if Bogardus' book was Hall's sole source of early information. Hall takes Bogardus to 1878, when he returned to London and shot before Queen Victoria 2 and back to America. As the complexity — and money wagered — continued to increase, Hall comments that,

"the clever sharpshooter could always devise new challenges by changing the number of birds to be killed, the time allowed, the position of the shooter, the distance, the boundaries or a seemingly endless number of other variables."

Hall lists more of Bogardus' feats, taken perhaps from Bogardus' book. Hall says:

"Between March, 1877 and January, 1879, Bogardus made eight appearances at New York theaters. In some of those he was the featured attraction, and the exhibitions he performed were indeed impressive."

Hall attributes this to the New York Times of March 31, 1877:

"At Gilmore's Garden Theatre in 1877 he undertook to shoot 1,000 glass balls in 100 minutes. Firing at a clip faster than one every five seconds, he destroyed the 1,000 balls in 78 minutes." 9

But what I liked was Hall's comment that

"a large wooden screen, covered with muslin to aid visibility, was erected to catch the shot."

As of now, the illustration for the cover of my proposed 600-plus page book on target balls shows Bogardus in London, on stage, shooting against a hanging screen.

But while some revenue came from the theater, Hall notes,

"The income for a performing marksman did not come solely from his pay or from the receipts of an exhibition. Generally, such shooters received money from companies for touting a particular brand of gun, powder or shell. Sometimes, such agreements were public knowledge, and the celebrity sharpshooter might lend his name to a particular brand: hence, Bogardus Championship Cartridges. At other times, such arrangements were kept secret, and the marksman would promote one brand while disparaging another as if he were speaking purely from the wisdom of his expertise."12

Hall attributes the above information to author Bob Hinman, but anyone who reads the 1870s-80s shooting publications soon recognizes that both the overt and subtle testimonials clearly were done for what would — almost 90 years later — be blasted as "payola."

But, as On Target! readers know, shooters — Bogardus, Paine and Carver in particular — were always challenging amateur shooters to try their hands — and guns, skills and wallets — to a match for big, big money. Hall agrees that

"another lucrative sideline to most of the feats and exhibitions was betting. Odds could be posted for different levels of difficulty within one exhibition. For example, during Bogardus' attempt to hit 6,000 glass balls, at least three different wagers were possible: even money for 6,000 of 6,200; 2:l for 6,000 of 6,100; and 10:1 for 6,000 straight."

(The 6,000-ball match never came off.) Hall says that,

"while it is unclear exactly how such wagering was conducted, it is obvious from the repeated references to odds and betting that the exchange of money played a significant part in these sporting-cum-entertainment activities."

(Pete Rose was simply born a century too late.)

But, back to the theater.

"Bogardus was not the only marksman to transfer his shooting skills to the exhibition arenas and theatrical stages. ‘Buffalo Bill' Cody received his nickname from his early profession of shooting buffalo for the railroads. He, like Bogardus, became a guide for hunting parties, and he eventually ventured onto the stage in a series of Western melodramas before gaining enormous fame in the arena of his wild west show. Annie Oakley supplied fresh game for restaurant tables before turning her skills to tournaments and exhibitions. In New York, marksman Ira A. Paine, the man from whom Bogardus wrested the American pigeon shooting championship, was a popular figure. Like Bogardus, Paine participated in unusual exhibitions: once he shot at baseballs thrown by a well-known pitcher and hit 57 of 98," somewhere around December, 1878. l3

Firing at baseballs? That's something new to add to my always-growing list of items shot by marksmen of the period. Hall attributes this information to the New York Times of Dec. 2, 1878, Page 2. (Wrong! I checked: It was Dec. 12, and the glass balls were thrown by James Devlin, a well-known baseball pitcher, and is detailed in the related story on Paine.)

"In fact, Paine and Bogardus carried on a publicity war of words for several years over who was champion of what, with Bogardus asserting that Paine was incorrectly advertising himself as ‘champion shot of the world.' " 14

Hall admits that,

"it was somewhat difficult to know just what championships were meaningful. Some events were held annually, like golf tournaments of today, and there could be many champions of such tournaments from different years. Other championships resembled title fights and could be held by only one man until he was defeated by another. Unfortunately, since governing bodies were virtually unknown, a reigning champion could easily forestall matches threatening to his title by demanding virtually impossible conditions from formidable prospective opponents ..." 15

Also, "a club, a manufacturer, or even an individual could arrange a tournament and label it whatever championship they wished."

But, I doubt if the audiences of the time, without CNN to investigate, were that critical of the various titles and challenges, either serious or sheer puffery. More likely, the boasts and bombasts merely whetted the viewing population's appetite.

Hall agrees, adding that despite lax regulations,

"shooting was undeniably a popular activity for participants and spectators alike, and it received extensive coverage in the press. The New York Times regularly carried news of shooting events on its sports pages, and major matches were frequently page one items. In addition, numerous specialty newspapers, many of which combined sporting and theatrical notices, provided information about the latest matches or challenges.

"The combination of news about sport and theater is not so odd as it might appear at first glance. Both sporting and theatrical entertainments enjoyed a boom period in the 1870s, both provided activities to fill the suddenly increased leisure time of the period, and both appealed to young, energetic gentlemen-about-town. Many of these weekly newspapers demonstrate the connection between theater and sport in their subtitles, hence: the Clipper; the American Sporting and Theatrical Journal; the New York Illustrated Times; the Best Theatrical and Sporting Journal in America; and Wilkes' Spirit of the Times, A Chronical of the Turf, Field Sports, Literature, and the Stage. ..."

Hall continues:

"While pigeon shooting was a popular sport for one segment of the population, it was opposed by others as a cruel and brutal enterprise. Since New York was the hub of much of the shooting activity, it also became the center of the opposition, led by Henry Bergh, president of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Bergh and his followers made every effort to disrupt pigeon-shooting matches in the New York area, to gain laws against them, and to draw public attention to what they considered a barbaric practice."

Even as its reporters covered the shooting events, the New York Times leveled its editorial condemnations at the killing of birds for sport. In one particularly telling jibe, the Times editorial page commented sarcastically:

"There are a few silly people ... who profess to be indignant and disgusted at the pigeon-shooting which has been in progress at Coney Island during the last week. A number of gentlemen connected with various sportsmen's clubs have been holding a convention with the object of blowing 20,000 pigeons to pieces with shotguns.

"They have labored steadily and manfully at this heroic task, but instead of receiving the admiration and thanks of a grateful community, they have actually been told that their occupation is a brutal and cowardly one. Such is the regard which awaits true heroism in this degenerate age." 18

The writer, Hall says,

"continued in this vein, blasting the pigeon shooters as forcefully as they had blasted the pigeons. Another editorial took specific exception to exhibitions, the only point of which, it declared, was ‘to accomplish the greatest amount of slaughter in the least space of time.' " 19

But, as anyone with any time spent learning about target balls is aware,

"this attention to the welfare of the animals and the effects of such slaughter on human participants and observers forced radical changes in pigeon shooting," says Hall, and, ultimately, brought on the rise — so to speak — of target balls.

"A variety of substitutes for live birds was tried," says Prof. Hall, taking his information from Hinman's "Gold Age of Shotgunning," "including metal birds, paper birds, and the Gyro-Pigeon, which was supposed to imitate the erratic flight of a live pigeon." 20

Hall then devotes a few paragraphs to the growth of target orb shooting, noting that,

"while the glass ball continued to be used in exhibitions and wild west shows through the turn of the century, it was supplanted for competitive shooting in the 1880s by the Ligowsky clay pigeon." 22

Hall continues Bogardus' story, taking him to Buffalo Bill Cody's wild west show, his short-lived partnership with W.F. Carver, Bogardus' own failed wild west show, the fire on (and sinking of) a Mississippi steamer, which destroyed a reported $40,000 in his equipment), and his later teaming with circus manager Adam Forepaugh, as well as other shows. 24 Hall also mentions Bogardus' "shooting gallery in Elkhart, after he retired from show business in 1891," but, sadly, makes no mention of the Chicago gallery, which was the goal of this whole trip through cyberland.

Bogardus' brief wild west show appearance with Annie Oakley in 1911 — Bogardus died in 1913 of Bright's disease — "was an oddly appropriate and significant finale," says Hall, "for neither he nor ‘Little Sure Shot,' who came from Darke County, Ohio, had anything to do with the frontier or the American West. Bogardus' fame derived from a shotgun, not a weapon of the frontier at all. Yet Bogardus, like Oakley, became a living representation of the dying American frontier."

Bogardus was the right man at the right time: His career spanned the gamut from flintlock musket (with which he began shooting as a youth) to hammerless double, the repeater, and smokeless powder, and he was articulate in his textbook on shooting, "Field, Cover and Trap Shooting" (ably assisted by Charles Foster).

Prof. Hall then goes on to, again, restate the important point about the absence of a language barrier:

"That representation was particularly important in the metropolitan areas of the East, where large groups of non-English-speaking immigrants clustered. They could watch and appreciate the wild west shows or the exhibitions of Paine or Bogardus without understanding a word."

On the third day of the year 1878, Bogardus achieved a record that still impresses today's historians and shooters (and is reported at the end of this report): 5,000 glass balls in 500 minutes.

When he recovered from that, later in the month of January, Bogardus was the featured attraction at Brooklyn's Tivoli Theatre "advertised as ‘der beste SchStze der Welt.' A month later, Paine played the same theater billed as the greatest ‘Tauben und Glaskugeln Scharfschhe der Welt.' " 25 (And, in 1889, Paine died shortly after giving a performance before an audience in Paris — see related story on Paine.)

Hall continues:

"In this way, immigrants were introduced to the gun as an accepted, even spectacular, part of the American scene. It is no wonder that in 1880 it is estimated that 17 percent of Americans could neither read nor write, yet 90 percent of the households owned a gun. 26 Similarly, from the wild west shows, the immigrants gained a highly theatricalized view of the American frontier."

Hall smartly notes that:

"Bogardus' feats cut across class lines as easily as the boundaries of national origin. In his days as champion wing shot, Bogardus played on the fields of the upper crust," yet "when Bogardus or Paine appeared on stage, it was usually at theaters such as the Olympic, the London, or Miner's Bowery, which catered to the lower classes.

"The cumulative exploits of Adam H. Bogardus were not the result of a theatrical sleight-of-hand. He was, without question, one of the finest marksmen of the 19th century,"

but, Hall says,

"Bogardus' significance does not end with his shooting, for his career presents a panorama of influences present in late 19th-century American life."

Bogardus, despite his Eastern and Midwestern roots, Hall says,

"became a representative of the West. He was a killer of literally thousands of birds for sport, who, because of changing public sentiment, helped to effect a mechanical revolution that eliminated live targets in the sport he dominated. He excelled as a shooter in competition, in exhibition and in performance, and within those formats he appealed to all classes" of his time.

Finally, Hall says, Bogardus

"was a master marksman whose legendary feats painted a vivid picture for streams of immigrants of the power and importance of the gun in American life."

While I credit Prof. Roger Allan Hall, he in turn credits "L.E. Corbett, technical gun editor of the American Shotgunner magazine, for his help in procuring information about Captain Bogardus." Amen.

Footnotes in the Hall

* Charles A. Bogardus was a minor shooter and unrelated to Adam Bogardus.

- 1 Biographical information is from Field, Cover, and Trap Shooting by Captain A.H. Bogardus (New York, Forest & Stream Publishing Co., 1891), passim.

- 2 William Bushell, The Life of Captain Adam Bogardus, privately printed without place or date noted, pp. 6-7. (I have searched for several years to find a copy of the above article; Prof. Hall was kind enough to e-mail me a copy of his. — R.F.)

- 3-8 edited out.

- 9 New York Times, 31 March, 1877, p. 8.

- 10, 11 edited out.

- 12 Bob Hinman, The Golden Age of Shotgunning (New York, Winchester Press, 1971), pp. 48-49, 74.

- 13 New York Times, 2 Dec. 1878, p. 2.

- 14 New York Times, 3 Sept. 1876, p. 2.

- 15 Hinman, Golden Age ..., pp. 68-69.

- 16, 17 edited out.

- 18 New York Times, 29 June 1891, p. 4.

- 19 New York Times, 26 May 1875, p. 6. It is quite possible that another inducement for the switch to inanimate objects was the increasing expense and scarcity of acceptable birds. At one match it was reported, "Some of the doves were so tame that they hopped on the ground on being let out of the trap, and they had to be frightened away to be shot." New York Times, 26 Feb. 1874, p. 3.

- 20 Hinman, Golden Age ..., pp. 46-52.

- 21 Removed

- 22 In his book, Step Right Up, (Garden City, N.Y., Doubleday & Co., p. 143), Brooks McNamara relates that breaking glass balls was spectacular, but simple since birdshot rather than a lead slug was used. (Simple? I would like to see McNamara try it. — R.F.)

- 23 Removed

- 24 Bogardus clipping file, New York Public Library of the Performing Arts, Lincoln Center.

- 25 George Odell, Annals of the New York Stage, X (New York, Columbia University Press, 1938), p. 457.

- 26 Hinman, Golden Age ..., p. 17.

- 27 Ibid., p. 65.

Meet the Teacher

At the time this story was compiled, Dr. Roger Allan Hall is a professor of communication arts/theater at James Madison University in Harrisonburg, Virginia. His work in the field of late 19th-century American popular theater, particularly how the frontier was presented in Eastern theaters, has been published in "Theatre Survey," "Nineteenth-Century Theatre Research," "Theatre Studies," and "Educational Theatre Journal." He is author of Performing the American Frontier, 1870-1906 (Cambridge University Press, 2001).

Bogardus shoots for the world

Jan. 5, 1878, copied from the Chicago Field

Captain Adam H. Bogardus has proven his claim of being the champion wing shot of the world. At Gilmore's Garden, New York, on Jan. 3, he accomplished his undertaking of breaking 5,000 glass balls in 500 minutes, a test of skill and endurance unparalleled. The shooting commenced at forty minutes past two o'clock, p.m., and at 31 minutes past 10 o'clock p.m., his task was successfully completed. The shooting was from two of his patent traps, at eight yards rise, and the excellent arrangements introduced added largely to the success of the match. Between the loading and firing there was scarcely any intermission, except when a new change of barrels was deemed advisable, and then the space consumed rarely exceeded more than half a minute.

At the breaking of the 2,000th glass globe he rested for 47 minutes and 15 seconds for refreshments, and recommenced shooting at 5 hours, 46 minutes and 15 seconds. He rested again at the end of the 3,000 score, at 6 hours, 54 minutes and 15 seconds for 20 minutes and 15 seconds, and resumed at seven hours, 14 minutes and 13 seconds, most of the time being taken up in adjusting the stock of his shotgun and in oiling the barrels, which were of Scott's manufacture, the weapon weighing 10 pounds, the cartridges used being charged with 31⁄2 drahms of powder and 11⁄2 ounces of No. 8 shot.

At the second recess it was found necessary to rehabilitate the wooded partition which prevented discharges doing damage to the Fourth Avenue side of the building by intercepting the shot. It was draped with white sheeting to throw the dark brown balls, as they were spun into the air from the trap, into bold relief. Immediately to the rear of the marksman a large calcium light was situated, which threw its brilliant rays in the direction of the sheeting, marking the course of the flying balls.

Captain Bogardus showed painful traces of his laborious task as the blackboard recorded the score by the thousand. His right arm was swollen and pained him very much. His assistants bathed and rubbed the injured member with *arnica and brandy, and he again resumed his work with great spirit, while his indomitable will was traceable in every line of his strongly marked features. After he had broken 4,000 balls, he took another recess, and expressed himself as feeling very much fatigued.

He completed the breaking of his first 1,000 balls in 1 hour and five minutes, his second 1,000 in 1 hour, two minutes and 30 seconds, when he rested for 47 minutes 15 seconds at 5 hours, 46 minutes and 15 seconds. He continued his labors with slightly slower results to the end, making six rests of short duration in the last 1,000 score. He was so exhausted toward the end that he was obligated to complete the last 500 points sitting on a chair.

He finally completed his task at 10 hours, 40 minutes, 35 seconds, thereby having 19 minutes and 35 seconds to spare.

In the total score 163 misses were recorded against him.

(*Arnica refers to Arnica montana, a mountain plant used for relief of bruises, stiffness, and muscle soreness in herbal medicine. Arnica is widely used as a salve for bruises and sprains, and sometimes as a tincture, for the same anti-inflammatory, pain-relieving purposes. It is still available in natural/health food stores.)